Kim Chung-up (김중업)

Fragments from a disappearing modernism

Part 3 of Ghosts Of Design explores a particular kind of modernist story that begins not with a building but with a landscape. Kim Chung-up’s life was full of them: the soft slope of Pyongyang where he was born, the industrial coastline of Yokohama where he studied, the compressed density of postwar Seoul, and, somewhere in the middle, the Paris of Le Corbusier’s atelier.

He seems to have carried these places with him like geological samples, turning them over in his mind as he imagined what a Korean modernism might look like. And although he spent time in Paris working at the atelier of Le Corbusier, when he returned home he did not try to copy and transplant concrete monuments. Instead he sought a hybrid path. A “Korean modernism” that could speak both the global language of modern architecture and the still be relevant in the local memory, terrain, climate, and light.

EARLY PERIOD

In the late 1950s, when Kim came back to Korea, the country felt suspended between ruin and momentum. His early university buildings from this period carry that strange in-between atmosphere. At Pusan National University and later at Konkuk University, he designed spaces that don’t assert themselves as much - long corridors washed in daylight, façades that feel slightly too open and functional minded.

A trace of his influences from working in Paris with Le Corbusier can already be seen in his first project back in Korea.

Sogang University Administration Building; 1959

A roof tO REMEMBER

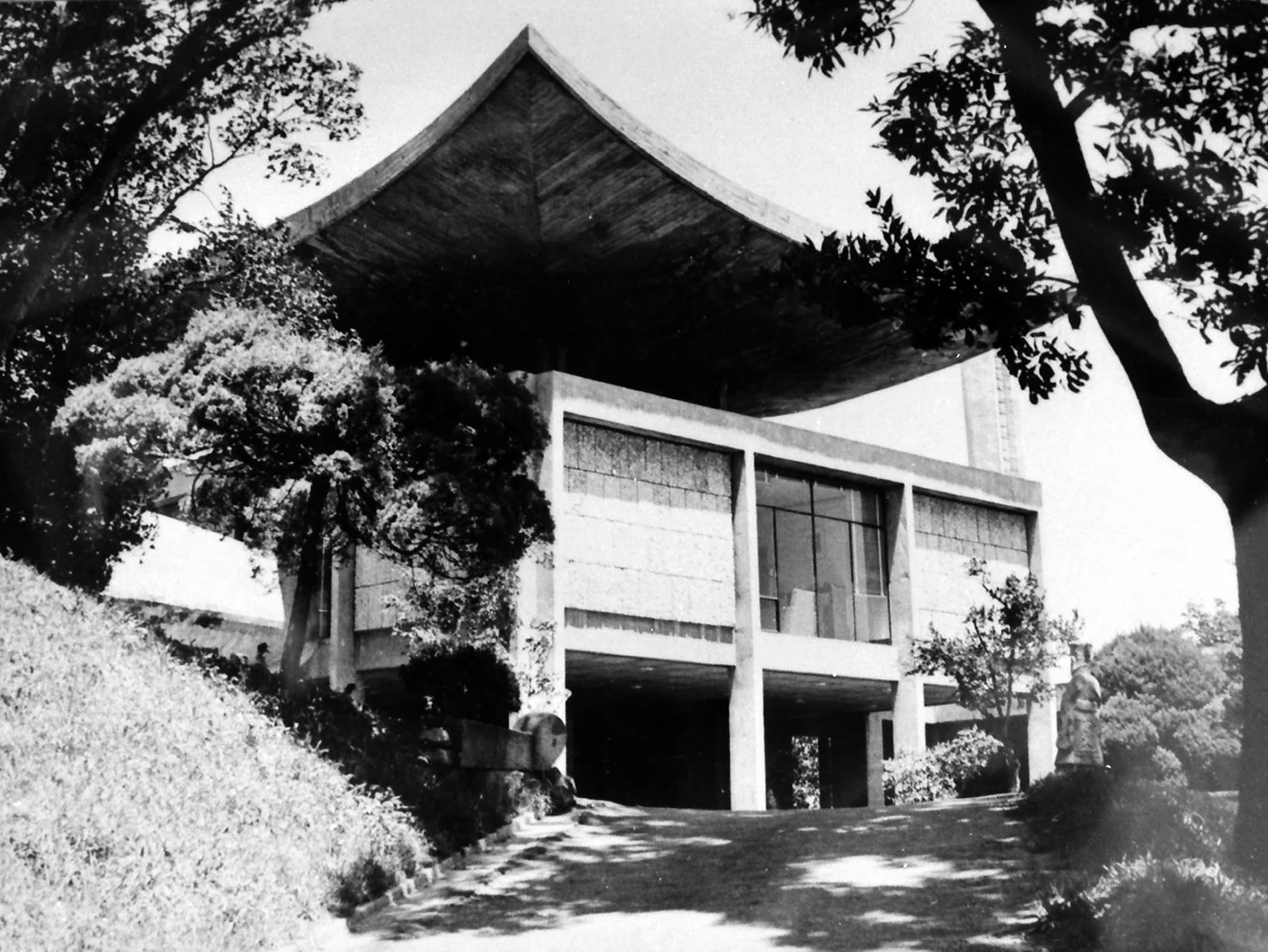

The French Embassy in Seoul is the quiet turning point in his career. It is a modern building in every structural and material sense - reinforced concrete, rational volumes, a clear Corbusian lineage - yet its most striking feature is the gently upturned roof. The gesture doesn’t mimic traditional Korean forms, yet it introduced a kind of architectural language that was entirely new to the area at the time.

The curve resolves several practical considerations: it mediates sunlight, softens the transition between interior and exterior, and shifts rainwater away from the façade. But beyond function, it also demonstrates Kim’s emerging belief that modernism could be filtered through regional sensibilities rather than applied wholesale. The Embassy becomes a place where international modernism and Korean spatial logic coexist within a single line of concrete.

Architecture as translation

Kim Chung-up’s career reads like a constant translation between languages that don’t quite match. Concrete and tradition, global ambition and local identity, wind and glass. He tried to reconcile Le Corbusier’s universal geometry with Korean rooflines and slopes. In doing so he accepted instability. Many of his early works have vanished.

Seo Obstetrics & Gynecology Hospital in Seoul 1961

House of Min at Bangbae-Dong, Seoul 1981

The French Embassy required renovation and parts were dismantled, surviving only as fragments relocated to a museum dedicated to his memory. His buildings are full of small experiments: stairwells that open to air, rooflines that waver between straight and curved, façades that try to find a rhythm between Korean shadows and modernist repetition.

Embassy of France, Seoul 1959

The island experiment

Kim Chung-up’s Jeju National University is one of those buildings that almost feels like a rumor. People who have never visited Jeju have still heard fragments about it: the sweeping ramps, the lifted white volume, the odd combination of breezeblock walls and soft, rounded windows. On paper it is an administrative building. In reality it is closer to a landscape, a structure that seams to be shaped by wind, salt and air.

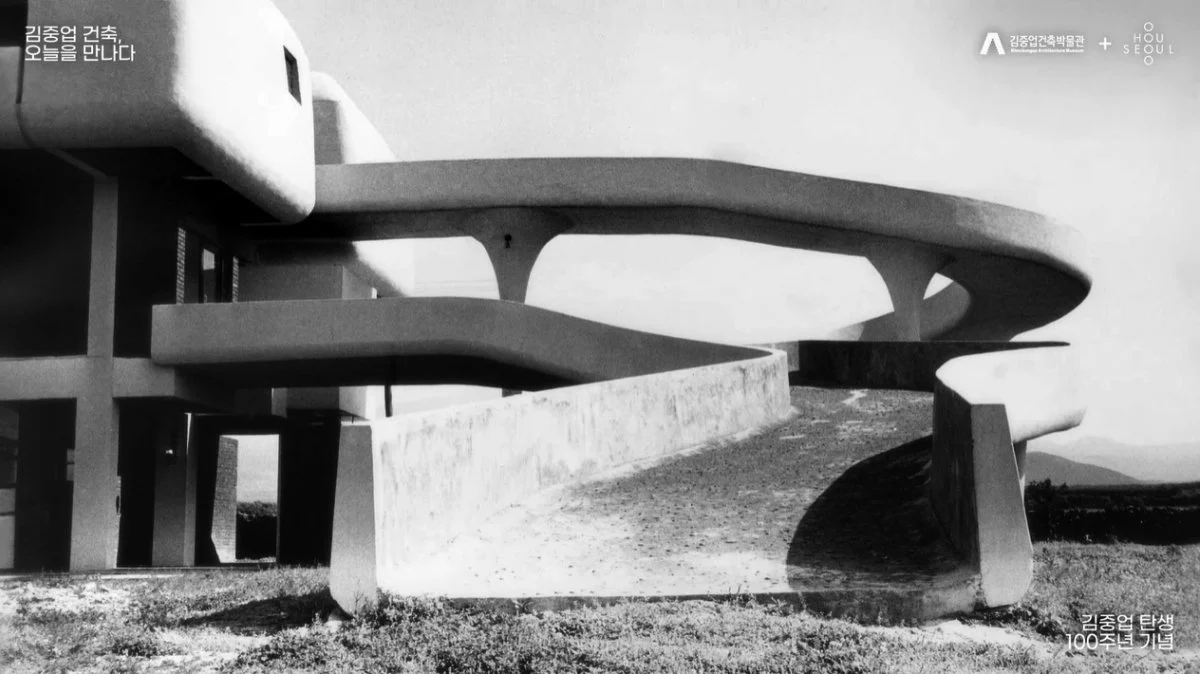

Jeju National University, demolished in 1995

The project was completed in 1962, at a moment when Jeju was far removed from the hyper-development that would later define Korean urbanism. Kim approached the site with a certain looseness, as if accepting the fact that an island cannot be over-disciplined. The building stretches laterally across the terrain, hovering above the ground on a set of surprisingly slender columns. This upward lift allows wind to move beneath it and light to enter from all sides, turning the complex into a kind of elevated platform rather than a fixed object.

At the eastern edge, a ribbon-like ramp spirals upward in a gesture that feels both playful and precise. It ties the building back into the slope, turning circulation into a spatial event. These ramps, combined with the elevated volumes and long projecting slabs, give the building an unusual sense of motion. Even in still photographs it appears poised to continue extending outward, as if responding to the island’s winds or the slow drift of passing clouds.

Kim’s design here feels uncannily free. Away from Seoul, away from the expectations of corporate towers and postwar reconstruction, he allowed himself a rare experiment. The Jeju Provincial Office becomes a moment where his influences briefly align. It is modernism without rigidity, tradition without nostalgia, experimentation without self-consciousness.

Many of Kim’s works wrestle with reconciling past and future. But this building does something different. It sidesteps the question entirely and creates its own vocabulary. A small government office on an island becomes a place where structure, landscape, and climate behave like collaborators rather than constraints.

If the French Embassy in Seoul was about controlled negotiation, the Jeju project is about release. It reveals what Kim Chung-up could do when the site allowed him to imagine freely, without the weight of national symbolism or urban pressure. It remains one of the clearest glimpses into his architectural instinct at its most unguarded - a building tuned not to ideology but to wind, light, and the slow rhythms of an island at the edge of the country.

The unresolved modernism

As I wrote earlier, Kim Chung-up never fully reconciled tradition and modernity. To me that’s precisely what makes his work interesting. He stayed in the restless middle, designing buildings that were neither purely international nor strictly Korean but something in flux, something still figuring itself out. In that sense, his work reads like a continuous draft - the unfinished manuscript of a Korean modernism that might have been, or might still be possible.

Many scholars have taken issue with his style of work. Figures like Lee Kyung-seong, Kim Won, and Kim Bong-ryeol have all argued that his architecture is “excessively expressive”. Yet if we take seriously Kim’s own insistence that he was reaching toward a new architectural era, the critique starts to feel misplaced. What once appeared extravagant now reads more like an early signal of the direction architecture would take in the late-modern and postmodern decades.