Marcello D’Olivo

Curves Against the Grid

Ghosts of Design continues with part 2! This time, we move to the north of Italy. Past the elegance of Gio Ponti, past the heavy shadows of Aldo Rossi, and into the strange world of Marcello D’Olivo. A name rarely spoken, even less understood.

Marcello D’Olivo (1921–1991) was a multifaceted Italian architect, urban planner, and artist from Friuli Venezia Giulia. Educated at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia, he graduated in 1947 and embarked on a career that defied conventional architectural norms. D’Olivo’s work is characterized by a deep integration of natural forms and mathematical principles, leading to a unique approach often described as organic and experimental. D’Olivo did not build by the standard rules. He built with rhythms. Spirals, waves, patterns borrowed from nature rather than logic.

If Jean-Louis Chanéac imagined parasitic buildings that clung to old ones, D’Olivo imagined cities that grew like seashells. He wanted his architecture to be an extension of the earth, not an imposition on it.

The Spiral as Foundation

D’Olivo believed in geometry. But not the kind of geometry found in rationalist facades or Fascist-era symmetry. He believed in the spiral. The curve. The organic unfolding of space.

He considered the spiral to be the fundamental shape of life: galaxies, shells, leaves, the cochlea of the ear. This belief found its purest form in Lignano Pineta, a masterplan for a coastal resort town near Udine. Conceived in 1953, D’Olivo’s design unrolled from a central nucleus, expanding outward in concentric rings. Roads looped like ripples. Buildings emerged between green spaces. The plan was visionary, not just aesthetically, but socially. It proposed a city that grew like a plant.

A few years later, it was actually built. But as the decades passed, commercialization and ad hoc development dulled its force. Some parts were paved over, others erased. Still, from the air, the spiral remains. A quiet trace of a radical idea.

Beyond Movements

Marcello D’Olivo did not align himself with any particular school or movement. This gave him a rare independence, but also meant his work often fell outside the architectural mainstream.

Most of his buildings were built near his hometown of Udine. They stand out for their unusual shapes, flowing lines, and clear departure from standard designs. Even in smaller projects, you can see his interest in geometry, contrast, and finding new ways to shape space. Below are some of my favorites:

Villa Spezzotti (Udine, 1955): A low-rise residential house built in collaboration with architect G. Marsilio. Though modest in size, it shows D’Olivo’s instinct for contrast: soft organic layouts inside, sharp diagonal facades outside. The relationship between light and shadow feels almost choreographed.

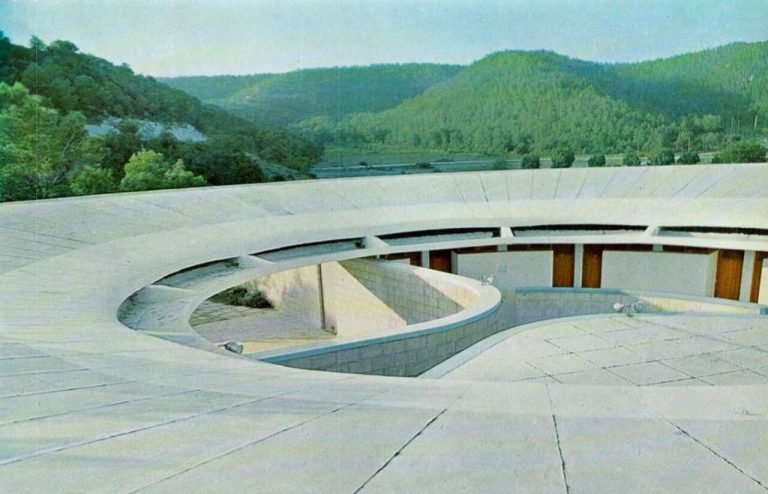

Villa Mainardis: Here, D’Olivo leans further into the sculptural. The house winds around an internal courtyard. Built in 1965 in Lignano Sabbiadoro, Villa Mainardis is one of D’Olivo’s most striking and imaginative domestic projects. A summer house like no other.

Lignano Pineta resort: some additional pictures.

Drawings, Dreams, and Strange Notebooks

While D’Olivo completed relatively few built projects, he left behind an extensive body of work on paper. His notebooks are filled with architectural studies, conceptual plans, and abstract diagrams that reveal a deep fascination with organic patterns and geometric rhythm.

These drawings show an architect thinking beyond immediate construction, exploring how form, motion, and structure could coexist in new ways.

In these notebooks, you really see how he thought… in spirals.

A Quiet Disappearance

Marcello D’Olivo died in 1991. His work was already slipping into obscurity. Today, most of his buildings remain undocumented. His theories go unread. His archives are scattered.

But his vision, the idea of a soft, organic architecture that resists the rigid grid still has power.D’Olivo didn’t shout. He drew. He curved. He resisted, quietly. He reminds us that design doesn’t have to be hard. That cities don’t have to be strict. That an architect can be something more than a builder.

The spiral city of Lignano Pineta still traces the coastline of northern Italy. While decades of development have softened its form, the original layout can still be seen: a quiet geometry spiraling out from its central hub.